Against the Master-Image: Toward a Phenomenology of Seeing

In an age dominated by assertive, spectacular images, this essay calls for a different kind of photography — one rooted in uncertainty, silence, and perception. Against the authoritarian logic of the master-image, it explores a phenomenological approach that resists capture and reclaims the act of seeing.

Photography, the moment it sees itself as capture, compromises itself with power. As soon as it claims to show, it begins to conceal. It is time to unlearn how to see, and to restore to the photographic act its share of uncertainty, trembling, and silence.

To photograph, in a phenomenological approach, is not to document an object, but to enter into relation with a phenomenon. It requires an embodied, situated gaze, one that does not aim to take an image, but to receive what emerges. In this light, the photographer becomes less an author than a witness: a being affected and transformed by what they perceive.

Phenomenology — in the work of Husserl, Merleau-Ponty, Maldiney — teaches us that we never access the world “as it is,” but through a process of appearance, in the first person. Consciousness does not observe a given world: it co-emerges with it. Photography, when understood through this logic, does not seek to illustrate an external reality, but to undergo the trial of a lived reality.

The Image as Perceptual Space

This dimension is clearly present in the work of Luigi Ghirri. Far from producing “strong” images, he photographs neutral places, peripheries, signs, banal objects. His work does not seek effect but emergence. Each image is a threshold, a suspension. The world never fully gives itself within them — it merely allows itself to be approached.

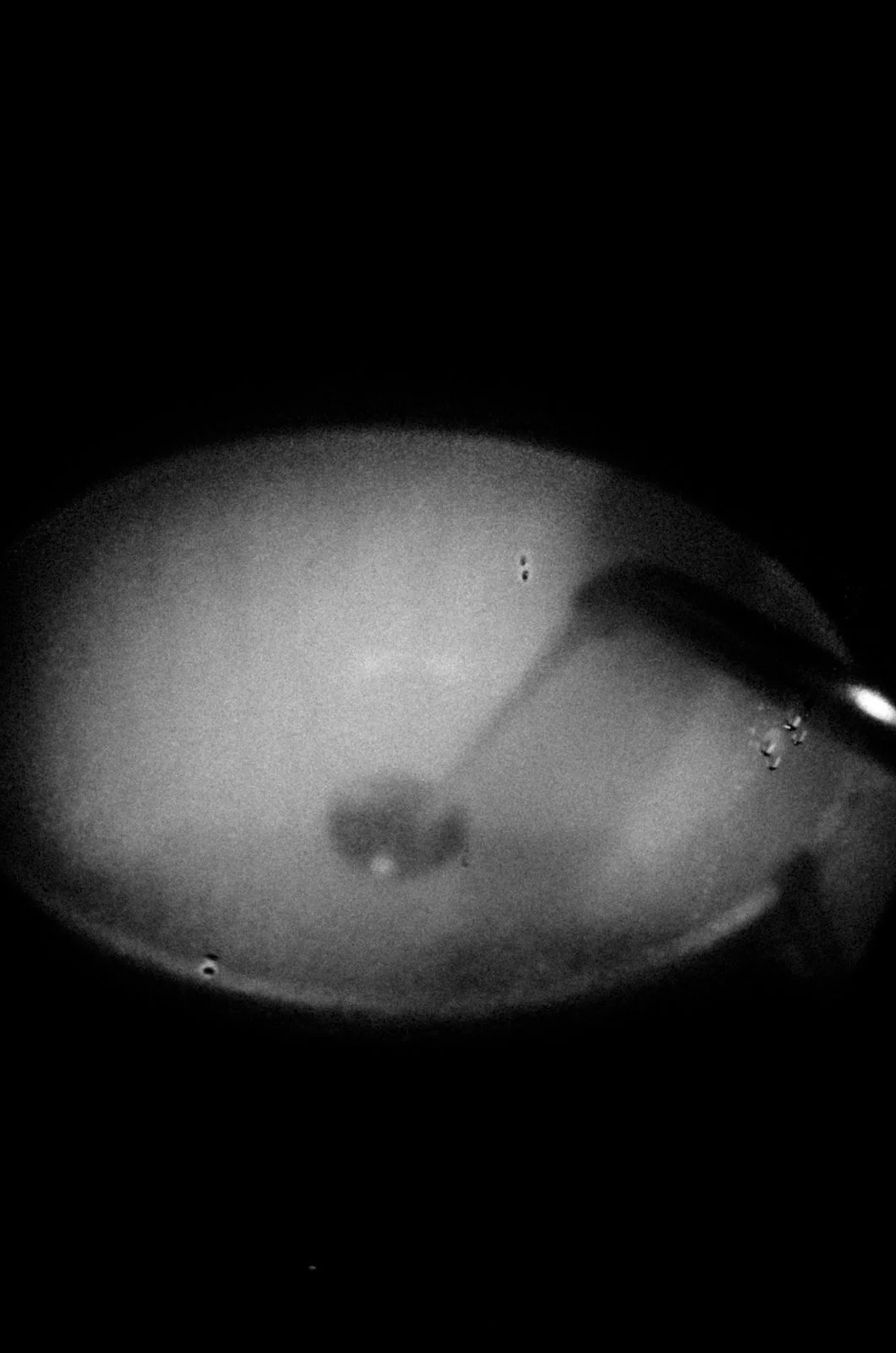

Rinko Kawauchi, in Illuminance, follows a similar logic: she does not describe; she gathers the emergence of a moment — a drop of water, a reflection, an animal caught in the light. A non-demonstrative photography, attuned to the vibration of things. These are not compositions — they are apparitions.

Likewise, Ray Metzker, through his play of shadow and light, shifts the image toward pure perception. It is not the streets he photographs, but the optical fold that manifests within them. The street becomes rhythm, tension, contrast — phenomenon, not representation.

The Image as Closure: A Critique of the Spectacular

In opposition to this phenomenological logic lies the empire of the master-image: the one that dominates, asserts, flattens. It already knows what it wants to say. It frames reality within a closed system of signs. It speaks loudly, but never listens.

Spectacular photography — whether in journalism, fashion, or institutional art — functions like a rhetoric. It captures, imposes, and neutralizes the otherness of the visible. It is immediately recognizable: efficient, striking, saturated with meaning. But it is also fundamentally anti-phenomenological, because it denies the perceptual process, the temporality of looking, the ambiguity of the real.

The most emblematic example is Andreas Gursky. His monumental, constructed, retouched compositions aim at a totalizing, often godlike view. The world is reduced to an observable, mastered, depopulated system. Everything is visible — and thus, nothing truly reaches us.

This logic dominates most images produced in commercial, editorial, or institutional contexts. It does not generate vision; it generates flow. It is fully compatible with advertising, the cultural industry, and digital platforms. It produces certainty — and in doing so, it kills doubt, disturbance, and emergence.

An Ethics of the Unapparent

Phenomenological photography, by contrast, is a practice of not-knowing — an ethics of attention. It does not seek to impose a form, but to make room for the formless. It opens a space of uncertainty, slowness, and floating perception.

It demands that the photographer withdraw as master, to become available to what resists: the glint of a wall, the density of a silence, light on skin. It refuses capture. It stands at the border between image and apparition.

And it is in this restraint that it becomes political. In a world saturated with explanatory images, this kind of photography suspends discourse, gives way to vision, and makes perceptual sharing possible. It does not seek to convince. It invites us to inhabit the visible otherwise.