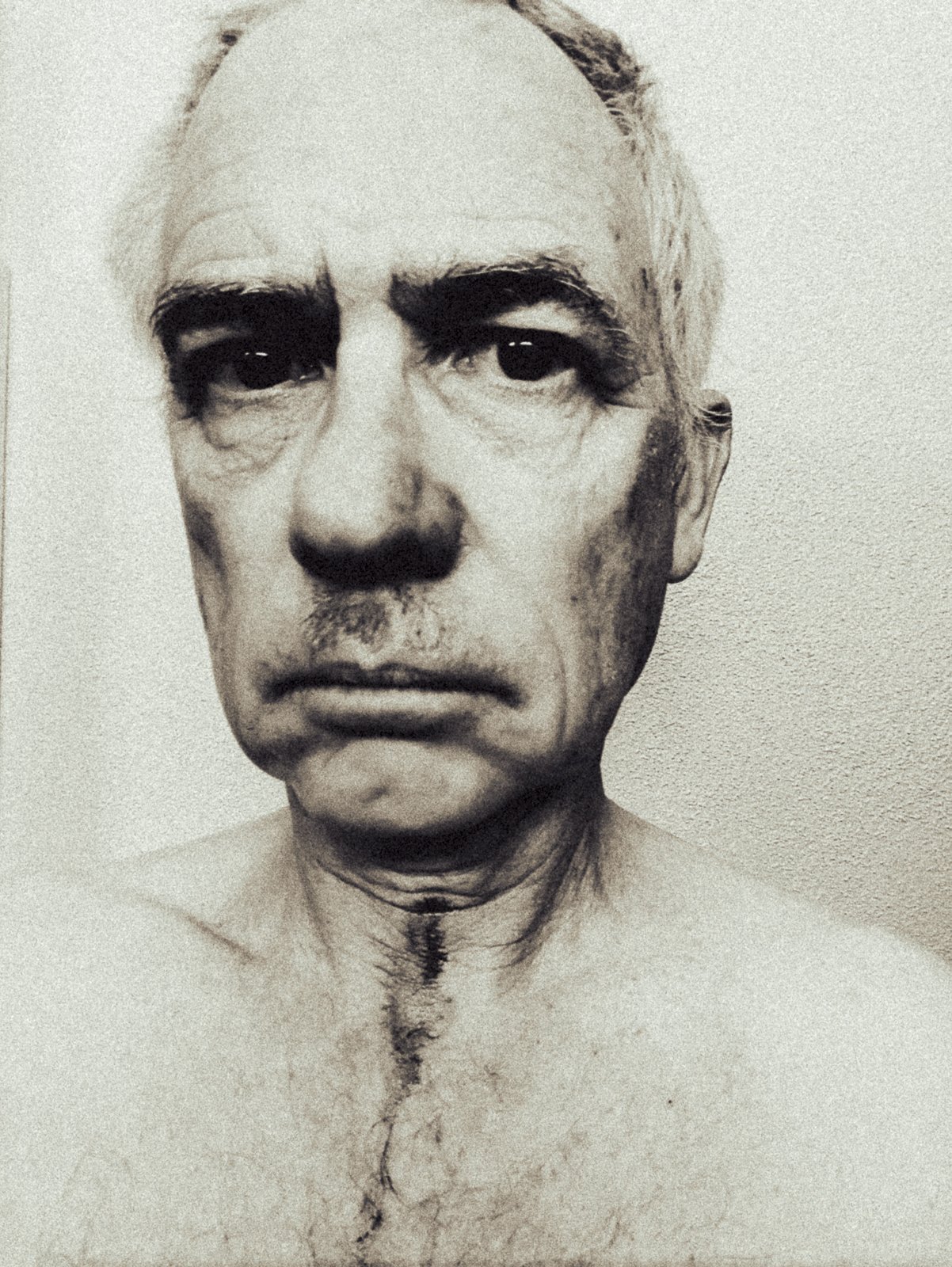

Me, in the Image. / Todtnauberg, 1:1

:Todtnauberg.

The series. The place. The hut. The words that never came.

(July ’49 — Celan meets Heidegger. A poem remains. A sentence is missing.)

I come from there. Or from nearby. So: not innocent.

The forest Heidegger gazed upon — I breathed it.

Not by choice. By origin.

The photo: not a pose.

But a stance. An attitude — in the flesh.

The gaze? — not a gaze, a counter-gaze.

(No, I’m not looking at you. I’m going through you. Until you look away.)

The image is rough, grainy. Like History under the nails.

Like shame, enlarged.

I put myself in the image —

not to be seen. But not to flee.

The place demands it.

The shadow of Todtnauberg: it’s not the weather.

Whoever can — let them look. Whoever cannot — let them turn away.

But one thing remains:

There is someone standing. And he remains standing.